One recent Saturday morning, I drove my 31-year-old autistic son Diego to a park for his group run with Achilles, an organization that promotes running for people with disabilities. As we walked toward the group, I suddenly noticed he wasn’t wearing underwear. I mean, you could just tell—the nylon shorts he had on offered no lining or support, clinging to the contours of his body.

I was instantly overcome with the blend of frustration and panic I would often feel when Diego was a child, but that I rarely experience at this point.

“For the love of God, Diego,” I said, trying to keep my voice calm as we turned toward the public restrooms to see if I could mitigate the situation by tightening the shorts’ drawstrings or something. “You’re already 31. Why? You know you can’t go places without underwear. What were you thinking!”

As is always the case when I become upset, Diego was repentant. “I won’t do it again. I won’t do it again,” he said, his eyes anxious and sad, and proceeded to break into prayer, “Our Father who art in heaven… I’m never going to do it again. God, I’ll never forget to put on underwear.”

His words instantly triggered the second stage of my reaction in these situations. My heart softened, guilt washed over me, and frustration gave way to tenderness.

“I forgive you. Let’s forgive ourselves,” Diego said, hugging me before exiting the bathroom. Diego has never used pronouns correctly when apologizing.

I informed the Achilles guides of our little situation just so they’d know I’m on top of things and that Diego typically wore underwear. They didn’t seem to care either way. I’d made a big deal in my head about nothing.

The underwear incident reminded me of the enormous fear of rejection, both of my son and myself, that I harbored for so many years. I guess that fear is still there to some extent.

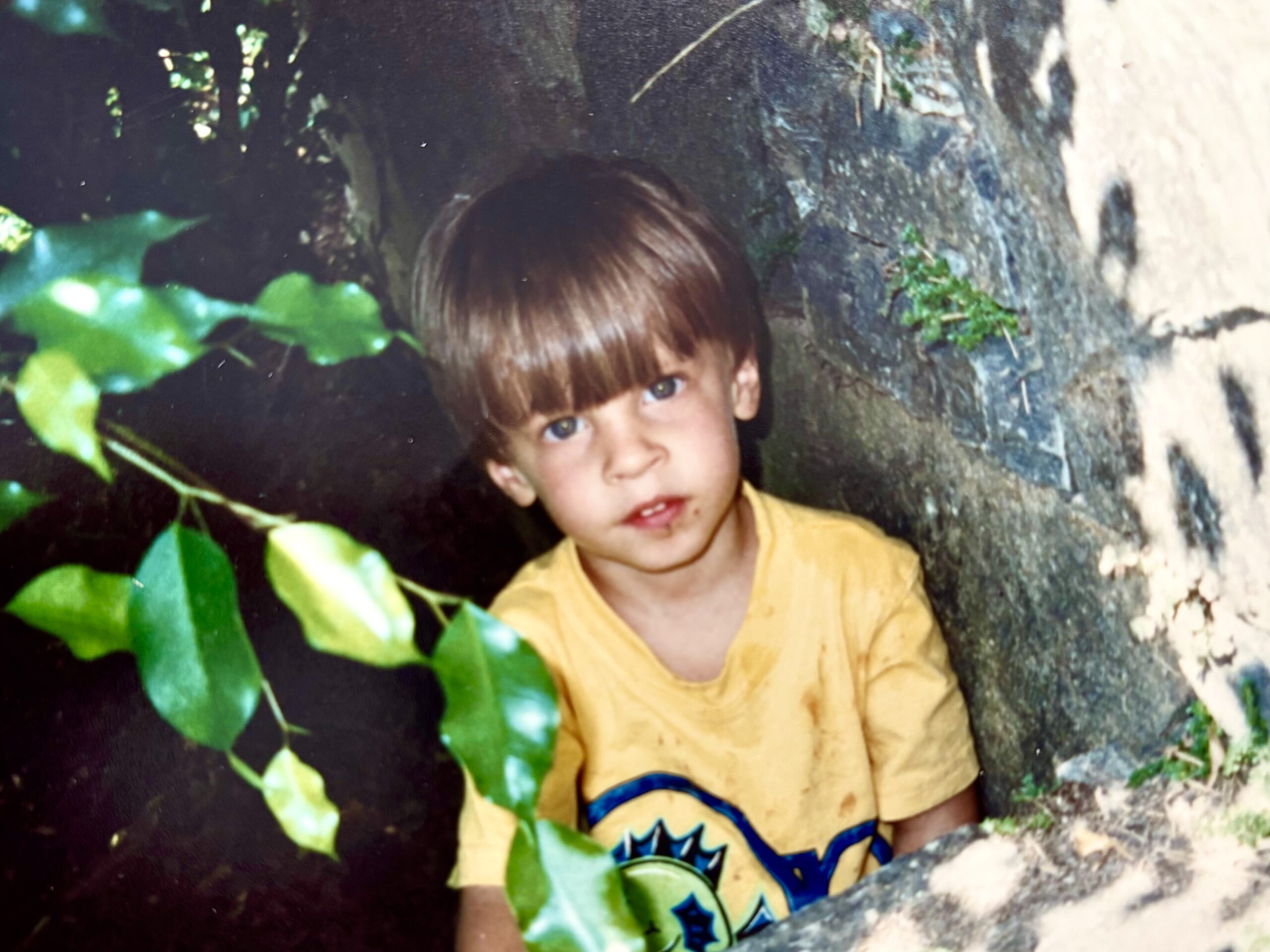

When Diego was a child, I strove to hide, minimize or make excuses for the things that made him seem different —his tantrums, running away, lining things up, ignoring me, looking at things out of the corner of his eye, covering his ears.

Truly, it was exhausting.

Still, I was convinced it was the right thing to do. So I kept at it.

I told myself Diego would eventually outgrow what was referred to as delays, disability, autism, deficits, pervasive developmental disorder, maladaptive behaviors, issues. I would be one of those rare mothers who found the magic formula to cure her child of whatever afflicted him.

Diego would learn to be normal!

Back then, I believed he would have no chance at normalcy if people treated him as if he weren’t normal. So I would only talk about what sounded normal: that he loved the water and had learned to swim, that he played chase with his aunt, slept through the night, could name a dozen whales, loved books, and was super affectionate.

A story I heard recently illustrates how useless my thinking was: A mother brought her autistic son to church for the first time, and he threw an all-out tantrum in the middle of the aisle as they made their way to the pew. While trying to calm him down, she saw a church helper heading their way and thought, It’s just as I feared. We’re going to be asked to leave.

The church helper leaned over and said, “I’m so glad you’re here. How can I help?”

This was not always my experience with the Church, but the point I’m trying to make is that many people want to know, help and embrace us as we are. Perhaps my attitude prevented others who wanted to be part of our lives from knowing, helping and embracing us.

All because I was intent on jamming Diego into the normal world, as if it were the only world, the whole world, the best world. Turns out it was not.