“What gets counted counts,” was, for me, the most memorable sentence uttered by any of my school administration professors. I wrote it in big letters, WHAT GETS COUNTED COUNTS, because these four words have been so relevant to my experience as a parent.

The first number you usually get when your child is born is his Apgar score, 60 seconds and 5 minutes after birth — 10 being the maximum score. After that, height, weight, head circumference, and percentiles for each, are measured and charted every time you take your baby to the pediatrician. If your child is perfectly healthy, that’s seven times over his first year, plus three more checkups his second year.

How we parents fixate on these percentiles! These are numbers we can easily understand and visualize, not only on our child of course, but also on the chart we are shown.

We talk about them and compare, with pride, worry or wonder -even after our children have grown up. Being tall is always positive: “Can you believe it? Jack is off the charts for height.” A much higher percentile for height than for weight, and never the opposite, is something we happily report to fellow parents: “Lizzie is on the 12th percentile for weight and on the 92nd for height.” Moving up the height percentile is also worth noting in public: “Mandy was always on the lowest percentile for height when she was a baby and she ended up being so tall!”

Thus begins our obsession (overt or not, conscious or not) with numbers and with how our child measures up to the “norm”.

Diego’s percentiles as a baby were great. In addition to the official numbers the pediatrician gave us at Diego’s checkups, I had a book or two about baby’s first year, and he was within the norms for sitting, rolling over, crawling, eating, all those skills that “counted” and that I tracked. He also seemed to be on schedule with language, a little on the late side, but still within the norm. Thus, even when I began to worry about the quality of Diego’s language and about his behavior, I did not really “count” that as too concerning for a good while. It was not something I knew how to count or that the pediatrician raised concerns about.

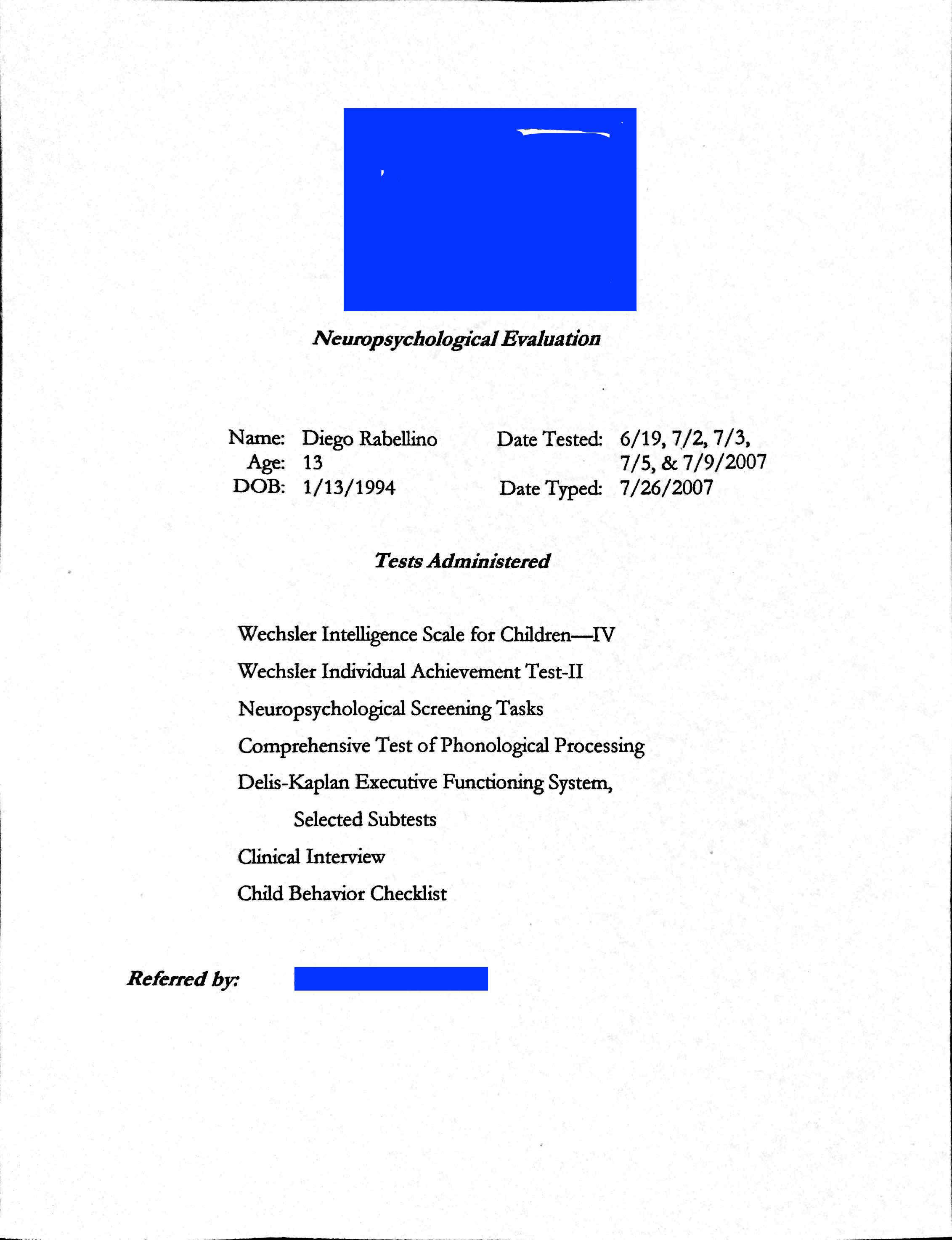

Once it was evident (at first to me, and only me), that all was not right, we turned to experts and special scores to confirm my suspicions and to tell us what to do. The numbers were always, ALWAYS, worse than I had anticipated and they devastated me. It was like a mini panic attack each time: my heart raced and I had to focus to breathe.

I have been presented with “scores of scores” about Diego’s abilities and functioning: academic, fine and gross motor, communication, adaptive, attention, behavioral, executive function and, scariest of all, cognitive -or what is commonly known as IQ (Intelligence Quotient).

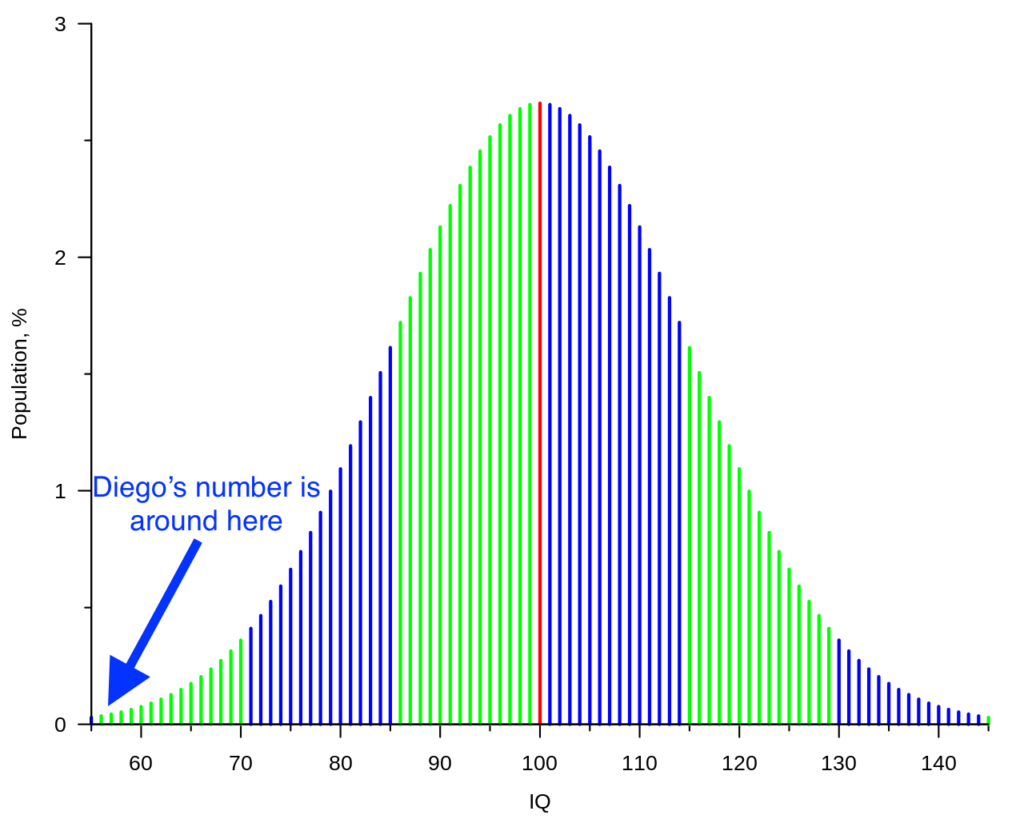

As the words in the abbreviation make rather clear, IQ is a number that we humans have come up with to measure “intelligence”. IQ assessment tools describe score ranges using various terms. In general, scores between 90 and 109 are classified as Average. Anything higher or lower is, obviously, above or below average. Depending on the IQ test, scores below 70 carry descriptive classifications such as Significantly Below Average, Very Low, Well Below Average, and Lower Extreme.

Officially (that is, according to the DSM 5), to be considered intellectually disabled, the individual must present deficits in intellectual functions (confirmed both clinically and through IQ testing) and deficits or impairments in adaptive functioning. Additionally, the onset of these limitations must occur during the developmental period.

Therefore, when a child or adolescent has an IQ score below 70, this often means that he has an intellectual disability, which is just the latest label for what, over the decades, has been known as imbecile, idiot, retarded, retard and mentally retarded. With time, each term turns offensive, either because we use it to hurt others or because we are ashamed of the condition. I think both. It’s hard to imagine name calling with “intellectually disabled” but, if the past is any indication, people will get creative, people will feel offended, and we’ll eventually need new nomenclature.

Just as the majority of drivers rate themselves as above average at the wheel, a statistical impossibility, we all like to think that our children’s IQ is surely above average. Below average is almost unthinkable to parents of children who do not present the syndromes associated with intellectual disability.

Moreover, IQ testing has been, historically, highly controversial. Throughout decades of the twentieth century, IQ was used to justify inequality and racism through specific policies like forced sterilization, bans on interracial marriage and educational segregation. Most horrifically, a low IQ in Nazi Germany meant extermination for thousands.

I grew up in the 1970s and 1980s in Caracas, Venezuela, and it was a time and place where one of the worst insults was to call a person “retrasado mental,” as in “¿Acaso eres retrasado mental?” (“Are you mentally retarded or what?”). The stigma, strong in my childhood, persists to this day.

Beyond the stigma, the literature reports that IQ is correlated -negatively- to career success, wealth, educational attainment, the probability of getting married, having a family, and even to the risk of ending up in prison and of an earlier death! Pretty discouraging stuff.

It is not surprising, then, that Diego’s IQ score would cause me immense despair. Diego’s IQ is around 53, technically in the Extremely Low range of intellectual functioning, the lowest possible classification. This number had great power over me and made me insanely sad and angry.

Diego’s low IQ score, more than any other, shattered my hopes of success and happiness for Diego. I clearly felt shame too. Once diagnosed with autism, I would readily tell anyone who asked about his special needs: “Diego has autism.” Never would I mention his intellectual disability.

Along with grief and shame, there was denial. I just could not disassociate my experiences from the narrow concept of “intelligence” that the number measured. How on earth could Diego not be intelligent? He remembers everything, I said to myself. He knows thousands of facts about animals and countries. He speaks two languages and can say hello in six. He sees people without bias and treats everyone with sincerity and kindness. He notices if any little thing in the room has been moved. Certainly a person must be intelligent to be able to do all of that!

I did not see the simple fact that intelligence has a different meaning in the context of experience and in the context of an IQ test. I was buried in my baggage and stuck on the word “intelligence”. At a conscious level at least, I did not fully understand that Diego’s unique mind and brain (like everyone’s) are infinitely more that his IQ. For this reason, it took me an awfully long time to accept, and later disregard the fact that Diego has significant cognitive challenges, that he indeed meets the intellectual disability criteria.

What gets counted counts, for better and for worse. For better, Diego’s low IQ number has counted in a positive and practical way. It has given him access to much needed benefits like money and services.

I am not against all testing, counting and numbers. After all, I am a teacher, and there is a lot of testing for all students, some of which is helpful. There is also some necessary testing of students with disabilities to prioritize services, improve teaching and to keep parents informed.

However, too often, the purpose of a good deal of testing is to advance personal agendas and views. Scores, especially those that are difficult to interpret by non-experts, serve as impressive proof. Twice during Diego’s school years, we paid good money to specialists to test Diego so that we could advocate for more, or different, services and placements. You see, children ages 3 to 21 are entitled to special education, but it is next to impossible for districts and parents to agree all of the time. And when a case is taken to mediation or a hearing, numbers are proof and count a lot.

A wonderful thing about Diego being an adult is that I have largely left behind the numbers that measure his capabilities. Now that Diego is 25 and no longer entitled to public education, money and services are not as extensive or dependent on so many test scores. Although aging out of public education meant cuts in resources, it has been freeing to focus more fully on what Diego actually does, on his experiences and preferences, instead of on what the system dictates that we should count.