I just want him to be happy and healthy. I just want him to be a good person. Isn’t this what we often say about our children? I used to say this about my sons Diego and Andres while Diego was still “normal” without giving it a second thought.

These statements are half-truths that we complacently believe until difficult realities kick in. Most of the time, what we truly mean is this: that we just want them to be happy, good, AND to walk, speak, read, cut with scissors, swim and maybe ski or play basketball; to be able to use the toilet, shower, knot a tie and make appointments; to get good grades and go to college; and to have the right friends and hopefully a family.

There’s no end to what we strive for in our children.

Had I truly been at peace with Diego being just happy and good, I would not have felt so much fear over the years. Before Diego turned 2, I feared that something was off, and I had my first taste of panic when his preschool teacher called to explain that she had “concerns”.

Was Diego happy and good? Absolutely.

I was crushed when the psychologist confirmed that Diego indeed showed developmental delays, and when he was eventually diagnosed with PDD-NOS (Pervasive Developmental Disorder- Not Otherwise Specified), then Autism Spectrum Disorder (same thing, different terms), then intellectual disability, and a few other labels.

Still, he was happy and good.

My stomach would churn and I had to excuse myself to go to the bathroom every time Diego’s special education program review was about to start. My throat would become dry and I would sometimes feel dizzy when I read testing results that showed the depth of Diego’s challenges and that incontrovertibly screamed that we were not dealing with “delays”.

Clearly, though, unhappy he was not.

By then, I no longer said that I just wanted Diego to be happy. My decisions were not based on any real consideration of the general meaning of happiness or what it may mean for Diego. Fear, in large measure, sustained my denial and stupid conviction that he would at a minimum grow up into a very quirky, yet college-educated, independent adult — as if any other outcome would doom Diego and us to a life of grief.

Now that Diego is a young adult, I ask myself: Did I actually think that going to college and being independent was the only way for Diego (or anyone else) to have a shot at experiencing happiness? I don’t think I was that obtuse. I now realize that I wanted these outcomes more for myself, for my own happiness. I sought what Daniel Gilbert calls “natural happiness,” the type that society favors and that results from getting what we want.

Also, I feared an unknown kind of future and I feared failure, regret and guilt — feelings which are not exactly compatible with happiness. For a long time, my success as a parent depended on Diego reaching the expected outcomes of the world I lived in, those that we can check off, measure and compare. Hence my frenzy to devote any amount of effort to Diego and his needs.

What if this or that therapy made all the difference? We had to try and, if we failed, at least we would not regret not having really, really tried. So we did try a lot of stuff. I took Diego to hours and hours of (mostly) proven therapies. We tried biomedical protocols: intravenous B12 injections, chelation therapy, secretin injections, and more.

Diego did not “catch up” though. Yet he is happy, and his heart is pure.

I see things differently now, of course. I believe that I made many good decisions as a parent even if I made them partly for the sake of my own happiness. In particular, some of the expended efforts helped Diego access and discover more of the human and natural worlds that fascinate him. However, I am glad to have gained a little bit of wisdom because living with fear, guilt and a relentless pursuit of “normal” as a requirement for happiness is destructive and no way to live. Diego is just 25 and I am twice his age. Both of us hopefully have a long life ahead still.

Also, it turns out that this damn pursuit of happiness is more problematic and confusing than you would think. Happiness is a moving target – even when we get what we think we want- as another recent experience made me realize.

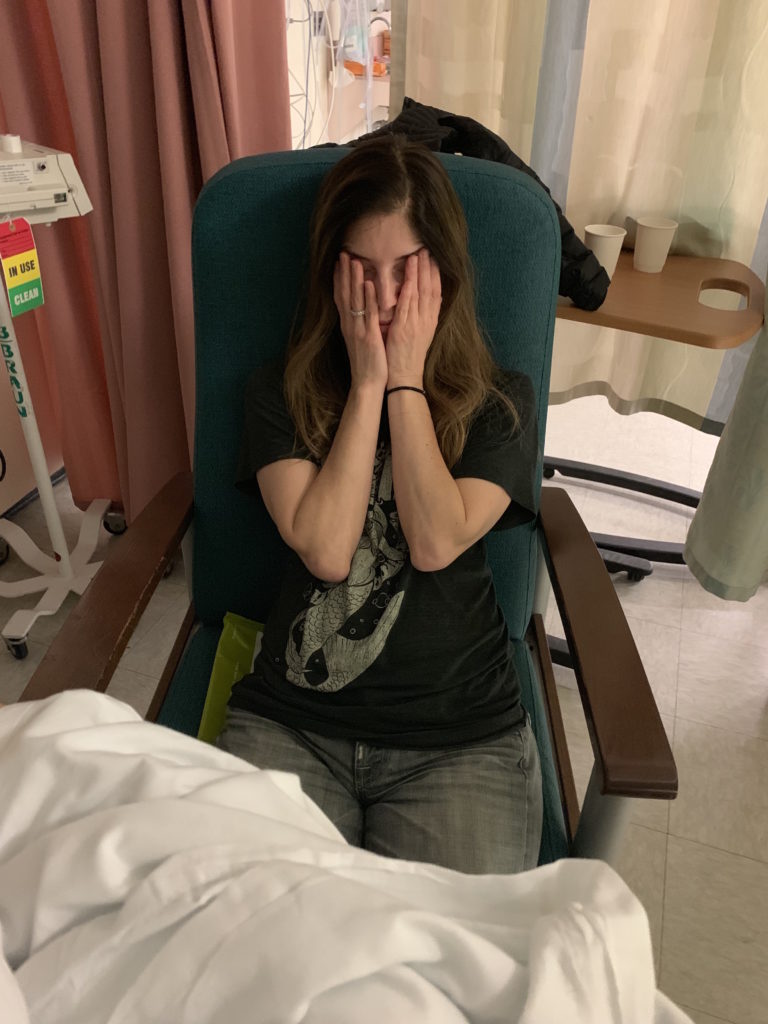

A few months ago I got a call that Andres (my “typical” son) was in an ambulance on his way to Bellevue Hospital in NYC. He had fallen and hurt his head. There was a lot of blood, a seizure and loss of consciousness. During the one-hour drive from Connecticut to the hospital, I almost made my husband crash as I writhed in my seat and loudly begged God for Andres to be alive. That’s all I wanted — for him to be alive when I got there.

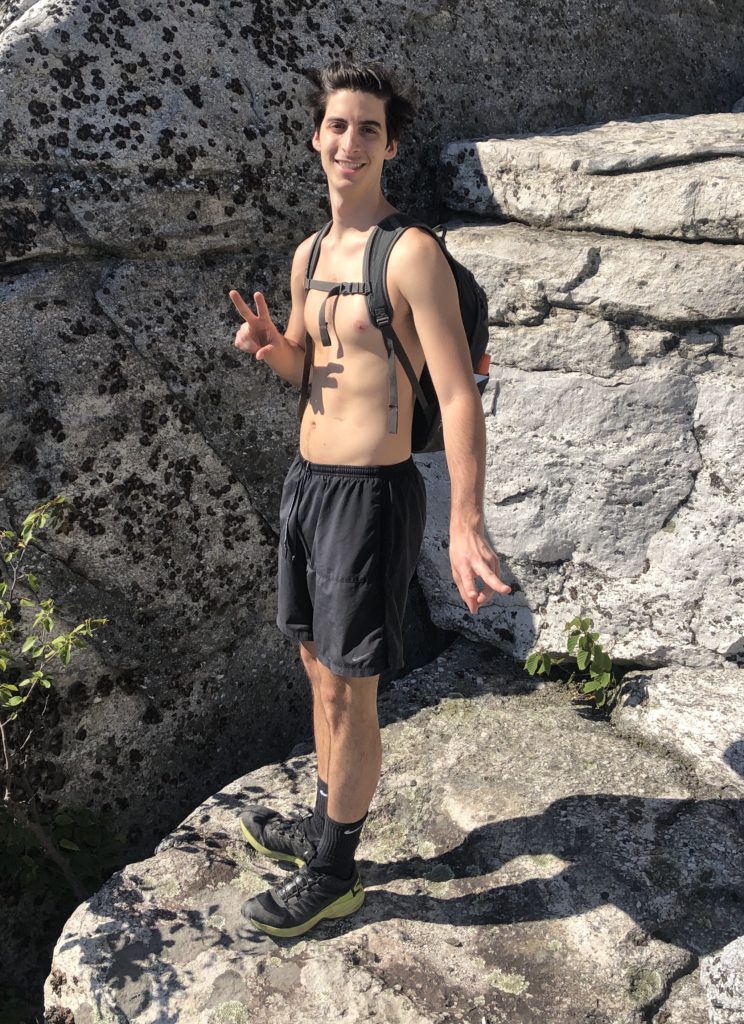

He was alive indeed! Did this make me happy? Almost euphoric actually. But my happiness requirement shifted to desperately wanting him to be able to “make sense,” that is, to accurately answer all the basic questions the medical staff and I kept asking him: Where are you? (New York, NOT Caracas). What year is it? What’s your name? Who am I? (He would say Daniella, my name, but could not say whether I was his sister, girlfriend, mom…). Once Andres was nailing all the questions, I indeed felt happy, yet the target shifted once again to needing him to be able to walk, then to read, use the computer, and so on…

As it turns out, Andres made a full recovery, and I am so very grateful and HAPPY. But does this mean that I would have been forever unhappy had the outcome been different? How about him?

I can’t speak for Andres obviously. In my case, however, I know that long ago I would have said, “Of course I would have been unhappy forever!” Today, my hard, honest answer has to be: I will never know for sure, even if my happiness would require my acceptance of an a priori less desired reality and finding a new path within it.

I now believe in what Gilbert calls “synthetic happiness,” that which we are capable of creating out of our actual experience, even if that experience is not what we had wanted in the first place. We don’t always realize this capacity for synthesizing happiness, but we do so more often than we would think possible. And the best part is that this happiness is just as real as the natural kind.