At some point, if you’re the parent of a teenager, you’ll feel like you can do NOTHING right. Such is the case even when, unlike my son, the teenager does not have autism and an intellectual disability. It’s like a cruel punishment for the privilege of feeling so much love for another human.

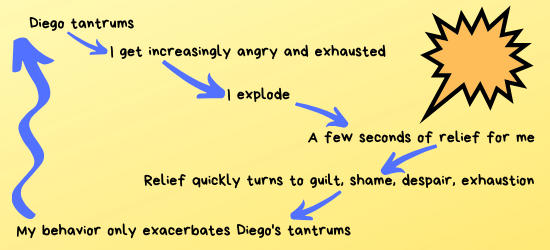

Much of the time during Diego’s middle teenage years, that’s just how I felt. All of the challenging behaviors Diego had ever had, plus a few new ones, emerged from his body and brain all at once, with maximal force, every day, multiple times a day. I lived in constant fear of detonating a hidden landmine. I had to tread ever so carefully as any minimally wrong move could trigger an explosion.

To make matters worse, I could never be sure which move would be the wrong one. Should I go into Diego’s room and kiss him goodbye before heading out, or should I try not to make a sound and just leave? One day he would start whining if I did the former; the next, he might go berserk if I did the latter. The unpredictability was draining.

If my answers to Diego’s repetitive questions changed just a tiny bit, he could tantrum like a 2-year-old. Every second we were together he stayed glued to me, stared at me and demanded my full attention.

I tried hard to stay calm and to draw upon my knowledge of behavior principles (I’m a special education teacher, for Pete’s sake), but too often I just lost it. I yelled back at Diego, said some nasty stuff, or worse.

And whenever I did this, I felt some relief.

The feeling, however, was short-lived and certainly not worth it. The deep guilt and shame that followed it were crushing. What kind of parent was I? What kind of twisted human found relief in yelling at her disabled child?

All this shame further drained me emotionally and physically, which undermined even more my ability to handle the inevitable next episode.

Here’s what it was like:

“As happens in any addiction, the behaviors we use to keep us from pain only fuel our suffering.” (Tara Brach, Radical Acceptance). I was caught in a peculiar addiction vortex. I would lash out at Diego for a brief moment of relief from the anger and despair that lashing out at him provoked! I was like the drunk in The Little Prince, who drank to forget that he was ashamed of drinking!

Eventually, I found a way out of this vicious cycle. I wish I could say that self-compassion was the main factor that helped me alter my behavior. However, the inevitable passage of time was what helped the most. Diego’s hormones leveled off; he grew emotionally; his medications were altered.

In fact, were you to meet Diego today, you’d say I’m making this all up!

Diego does need a lot of support still, and many times he drives me nuts. I have learned, though, to approach each challenge separately and to practice self-forgiveness. I turn the page quickly, so to speak. I do this for him, but mostly for myself, although both are related.

The practical result of learning compassion is this (again Radical Acceptance): “When we are not consumed by blaming and turning on ourselves or others, we are free to cultivate our talents and gifts together, to contribute them to the world in service.”

I now recognize the counterproductive cycle I went through. I believe that shame and self-blame are two of the feelings that most limit joy and personal growth. Such was the case for me as a parent.