I recently showed my 26-year-old son Diego an abstract painting with lots of red on it and asked him what it showed. Without a moment’s hesitation, he declared it a pizza.

A decorative wall plate with a blue horse on it, he labeled “a mustang, like Spirit,” from the movie Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron.

Diego’s imagination is pretty interesting, not just for an adult, but for someone any age. Diego has autism and a way-below-average IQ. These differences, as well as his personality and life experiences, certainly make his mind pretty cool.

It’s not that Diego has the imagination of an individual whose age corresponds to Diego’s IQ. It’s more that his imagination originates from the brain of a person whose “cognition” has stayed at, say, the 8-year-old level for 18 years.

Over these 18 years, Diego has grown a great deal, enriching his mind and imagination through tons of experiences, hormonal changes, accumulation of knowledge and facts -integrating it all into a pretty original framework.

The same thing happens to us adults with average cognitive skills. It’s just that we integrate it all into a framework informed by a cognitive level that’s “normal” — that is, the most common, the norm.

Diego’s mind and imagination, then, cannot be like a “normal” 8-year-old’s at all. It can’t be, since humans are only supposed to stay that age for exactly one year. Nor can it be like that of a 26-year-old, because his cognition is that of an 8-year-old!

Part of the ability to imagine involves having fewer established categories. That’s one of the reasons children are imaginative, and why Diego retains a child-like imagination.

We all organize experiences, views, feelings and the physical world into categories. As children, the categories are few: happy/sad, pleasant/ unpleasant, parents/all other adults, clothes, food, animals and such.

As we grow older, we organize it all into increasingly complex categorical structures for everything, from the feelings we experience to which groups of people we should care about and how much.

Heck, we even create hierarchies of categories, which gets us into a lot of trouble. Take religion. The category of Christians branches out into Christians that interpret the Bible literally and those who don’t, Christians who support the death penalty and those who don’t -and so on.

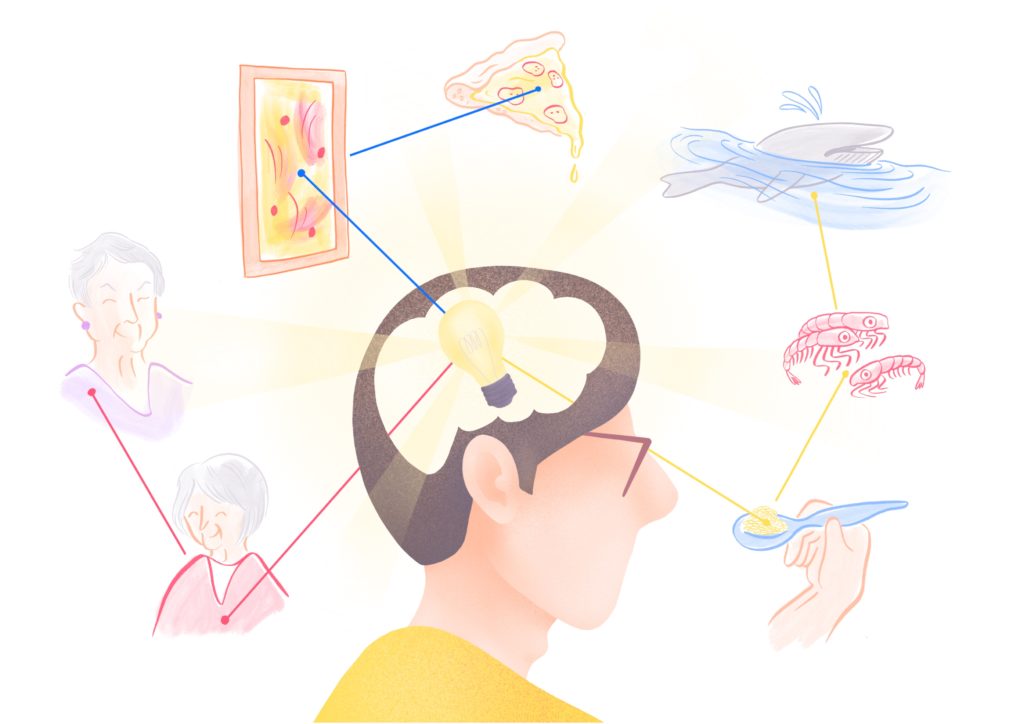

Back to Diego. I believe Diego’s level of cognition has kept him from developing a complex “adult” system of categorization. His imagination is not hindered by rigid categorical reasoning. Instead, he relies more on associations in his relation to physical and emotional experiences.

The way I see it, Diego’s peculiar imagination originates in his associative, as opposed to categorical thinking.

And it is Diego’s autism which probably accounts for the majority of the associations he makes. Autism’s diagnostic criteria includes: “Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus (e.g, strong attachment to or preoccupation with unusual objects,…).” ( DSM-5)

Diego’s interests include animals, anything Disney, superheroes, travel books, geography, birthdays and movies. I can’t think of any interest he has abandoned ever since he was around 4 and suddenly stopped playing with cars.

He doesn’t replace, he adds on. Average adults usually don’t stay obsessed with the same topic for as long as Diego.

And does Diego ever make associations to his excessively circumscribed or perseverative interests! His language is packed with such associations:

- Like a baleen whale, Diego eats krill when he’s having cereal or paella.

- When he chokes or vomits, Pinocchio got stuck in his throat.

- According to Diego, Abuela looks like Judy Dench, his uncle like George Clooney, and his cousin like Mama Imelda from Coco.

- Diego prays to the Virgin Mary, Nonno, Juan, Tia Margot, the Buddha, Gino, Allah — anyone who’s no longer in this world but in heaven.

- Diego recently showed me he had a scar (just a scratch, really) “like a hippo’s”.

- A puddle reminds Diego of “Lake Tanganyika”.

- At home, I’m the “queen” and my husband is “his majesty”.

- When Diego’s leg trembles, it’s like “an earthquake”, and when he walks around the house he’s “patrolling”.

Yes, more than anything else, Diego’s disordered language is a window into his imagination.

Diego’s sensory experience is atypical and influences his mind as well. This has to do, I think, with another autism criteria: “Hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input or unusual interests in sensory aspects of the environment.”

Though he’s grown out of a lot of his sensory “issues”, Diego’s hearing is still markedly different than the average person’s. He perceives certain sounds as painful (especially hangers sliding along a metal rod) and doesn’t distinguish much of the main sound from the rest of the composition.

Diego has a nice voice but it’s hard for him to sing through a whole song in a “normal” way. Unlike most of us, he doesn’t differentiate the lyrics and melody from the rest of the auditory stimulation that, together, make up a song.

When Diego sings something, he includes all the sound effects and background sounds that accompany the song. It’s like he hears it all as foreground.

He needs to practice, practice, practice to sing just the words. He’s working on his repertoire though. So far, he’s doing very well with Go the Distance (Disney’s “Hercules”), and Remember Me (Disney’s “Coco”). He has also mastered Happy Birthday, and leaves his rendition of it as a voice message to many people on their birthday.

For Diego, background and foreground just aren’t too distinct. Perhaps this is why he’ll immediately notice when something’s missing in his room, or when I move things around?

Diego’s imagination has room for visual and auditory details we wouldn’t notice because we’re used to focusing on the forest and not the trees.

Finally, I do think Diego’s personality imparts an alternative wisdom or intelligence to his imagination. He can’t imagine why people spend so much time criticizing others, for instance. Or why couples stop being friends when they break up. Or why you’d stop talking to people just because they’re dead.

Diego’s imagination will not solve any practical problems, like solving for X or developing a vaccine for COVID-19.

However, because it operates in a singular way, it does allow a glimpse into how the brain operates and into a mind that’s pure and good.

Based on an article published on the Medium publication Illumination.