I recently finished a book that blew me away: Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error, by journalist Kathryn Schulz.

For starters, Being Wrong reminds us that the most mysterious object in the whole universe is located right between our ears, encased in the 3D puzzle of bones we call the human skull.

Yes, the brain. So, you ask, what, specifically, is Being Wrong about? Well, in the author’s words:

“About how we as a culture think about error, and how we as individuals cope when our convictions collapse out from under us.” *

Here, then, dear explorer of the human brain, are the ideas in this book that rattled my thinking in some way.

Why We’re Prone to Error

1. The feeling of “knowing” is powerfully seductive

“It fills us with the conviction of rightness whether we’re right or not.”

We just love the feeling of being right. We don’t flatly say “I knew it” when an event proves us right. We exclaim the three words with glee, whether what we knew was joyful -as in “I knew you’d land the job!”- or tragic -as in “I knew he’d end up killing her.”

What’s more, we’re also great at noting we knew others were wrong all along! Yes indeed,

“We positively excel at acknowledging other people’s error.”

Nothing can quite match our smugness when we say, “I told you so”, especially when a spouse or parent is involved. I can’t count how many times I’ve said to my husband “I told you not to have the third slice of cake/glass of wine/serving of spicy pork ribs. I knew you’d be sick.” I’m almost glad he’s sick.

Even if we’re nice enough not to throw the comment to a person’s face, we take deep pleasure in being proven right — and the other person wrong.

Basically, we’re programmed to feel right and to enjoy the feeling.

2. It’s hard to notice and predict our own wrongness

“Although we understand in the abstract that errors happen, our specific mistakes are just as unforeseeable to us as specific tornadoes or specific lighting strikes.”

Several factors conspire to blind us to our mistakes, whether past or future. For instance, we go through life as if what we see, hear, taste, or feel always captured the whole picture.

And yet,

“Even the most convincing vision of reality can diverge from reality itself.”

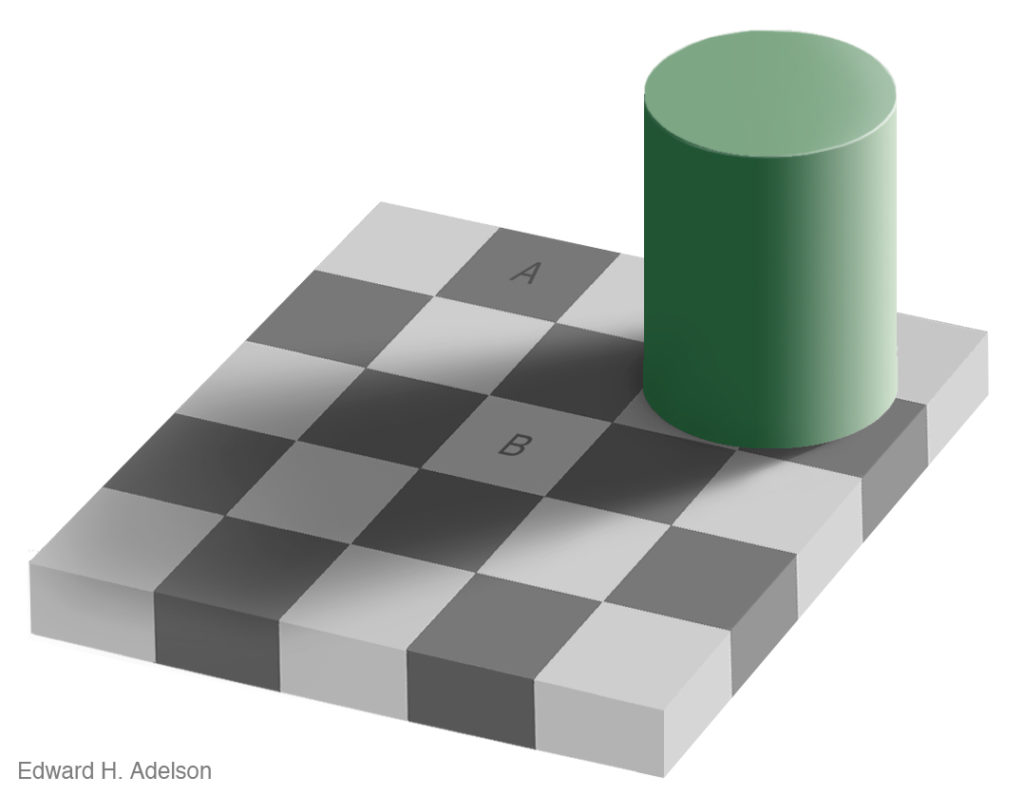

That’s what illusions — “failures of perception,” as Shulz calls them — show us.

The Checkershadow Illusion (created by MIT professor of vision science Edward Adelson) is one great example of how we can be fooled by our sense of vision even when we know it’s fooling us.

Fact: Square A and square B on this checkerboard are the very same color. Literally the same shade of gray.

Don’t believe me? Print the board and cut out the squares. In fact, print out a bunch and have your friends and family do the same. It’ll be fun, I promise.

Just as we feel all-knowing when it comes to our senses, we’re arrogant when it comes to our memories and convictions. I don’t know about you, but I’ve had countless exchanges with loved ones that go something like this:

Me: “Yes I did.”

Them: “No you didn’t.”

Or like this:

Me: “I did NOT!”

Them: “You did TOO!”

3. The feeling of being wrong is unpleasant

“Nobody but you can choose to believe your own beliefs. That’s part of why recognizing our error is such a strange experience: accustomed to disagreeing with other people, we suddenly find ourselves at odds with ourselves.”

Yeah, shame and denial are often part of the “being wrong” experience. In extreme cases, we persist in our denial and never admit that we were wrong (at least to the world). This is obvious in relationships, where each side attributes all the blame to the other.

Thus, we hide our mistakes and refuse to accept them— which only makes us prone to future errors.

4. We confuse our identities with our beliefs and don’t seek to understand beliefs that don’t match ours

“Our beliefs are inextricable from our identities.”

Often, such beliefs are held in clusters associated with specific communities from which we derive our sense of identity and belonging.

“It is hard, excruciatingly hard, to let go of the conviction that our own ideas, attitudes, and ways of living are the best ones.”

Most of us are supremely unmotivated to educate ourselves about beliefs with which we disagree. Additionally, far from making us reevaluate our beliefs, external opposition — especially opposition that we perceive as threatening or insulting — tends to make us dig in our heels even more.

5. Beliefs are easy to form but mighty hard to discard

Humans “have the capacity to reach very big conclusions based on very little data.”

This capacity, known as inductive reasoning, is incredibly helpful. Think about it: As young children, it allows us to quickly generalize grammatical rules and to instantly recognize all manner of spoons as spoons after experiencing just a couple of them.

There are, however, significant drawbacks linked to our wondrous reasoning skills. As Schulz warns,

“Since the whole point of inductive reasoning is to draw sweeping assumptions based on limited evidence, it is an outstanding machine for generating stereotypes.”

If your first two encounters with dogs involved getting bitten, you might sense all dogs as dangerous, right?

Even worse, you don’t even need to experience situations firsthand to reach big conclusions and adopt negative stereotypes. If your mom screams with fright when a dog comes close and tells you stories of how vicious they are, you might also be scared of them.

Another unfortunate effect of inductive reasoning is this:

“Although small amounts of evidence are sufficient to make us draw conclusions, they are seldom sufficient to make us revise them.”

We hold on to our convictions for dear life and don’t listen to – and much less seek out -counterevidence. When we do acknowledge counterevidence, we simply label it “an exception that proves the rule”-unless, of course, it proves our belief, in which case we posit it as evidence for it!

6. Being wrong is frowned upon

Being wrong “appears to be a key means by which kids learn, and one associated as much as anything else with absorption, excitement, novelty, and fun.”

Oh, to be young… Inevitably, we grow up and the window of time where making mistakes was not only OK but also celebrated closes forever.

For grown-ups, being wrong can damage or even destroy reputations and careers. Deservedly or not, those who would profit from our downfall will exaggerate our wrongness. Then, of course, there’s the perverse pleasure of witnessing the fall of someone we dislike or envy. We humans are malevolent like that.

No wonder small errors can turn into epic failures. Instead of admitting incipient mistakes to ourselves and the world, we rationalize or hide bad decisions until the mistakes pile up and turn into colossal failures.

Why Wrongness Makes Us Better Humans

1. Human wrongness is inseparable from comedy, art, and science

“Our capacity to err is inseparable from our imagination.”

Comedy not only captures our wrongness but also exaggerates it and imagines every possible way we could be wrong. That’s why movie bloopers are funny and why comedy often looks like movie bloopers.

Is art an accurate reflection of reality? Of course not. Cave painters did not replicate mammoths precisely. And it’s not because the artists were bad. Picasso’s depictions of humans are all wrong.

As for science, progress is impossible without getting things wrong. When it comes to the frontier of science, which is where discoveries and progress happen, “The day you stop making mistakes is the day you can be pretty sure you are no longer in the frontier, ” asserts Neil deGrasse Tyson in his MasterClass, Scientific Thinking and Communication.

We enjoy art and do science because it lets us be wrong and play with our imagination.

Being right all the time would be boring and limiting.

“Being right might be gratifying, but in the end it is static, a mere statement. Being wrong is hard and humbling, and sometimes even dangerous, but in the end it is a journey, and a story.”

2. Being wrong makes us humble and more empathetic

“Our mistakes, when we face up to them, show us both the world and the self from previously unseen angles, and remind us to care about perspectives other than our own.”

Being wrong is unpleasant, embarrassing, and costly. And yet, it’s one of those experiences that ground us.

A lot of us become less arrogant as we get older. I suspect it’s because we’ve been wrong enough times to accept and know we’re not as smart as we thought.

And isn’t it peculiar how our mistakes make us relatable and help us relate? I don’t know about you, but I love to talk to people who’ve messed up in similar ways as me. When I get together with other parents of grown special needs children, for instance, it’s immensely comforting and, yes, fun, to share stories of how incredibly wrong we were about disability and parenting.

When you meet people or read about their experiences, aren’t you instantly turned off by those who seem to have gotten it all right? People who put themselves down and own their wrongness are relatable because we find them, well, human.

Final Thought: Cultivate Doubt

“Doubt is the act of challenging our beliefs.”

Surely there are mistakes we must seek always to avoid, and those that cannot be forgiven without accountability. Having the wrong tooth extracted or the wrong leg amputated comes to mind. So do airplane design flaws leading to plane crashes and the deaths of hundreds of souls.

Then there are those mistakes stemming from our reliance on our inaccurate memories and perceptions, or from rigid convictions that blind us to any counterevidence.

Whatever the nature of our errors, one thing’s for certain: we will never be able to eliminate them. We are, and always will be, wrong about things.

It behooves us, then, to learn from and own our mistakes while cultivating a healthy measure of doubt. As Schulz notes,

“Remembering to attend to counterevidence isn’t difficult; it is simply a habit of mind.”

*Unless otherwise noted, all quotes come straight from Being Wrong