People who spend any amount of time with parents of school-age children have known mothers and fathers whose children can do no wrong. They explain away any reported fault in their children by blaming others and attributing ignorance, jealousy or even malice to the messenger. These parents can be really annoying. We shake our heads and think that we would never deceive ourselves like that.

The truth is, though, that we are all subject to the powerful phenomenon of denial, no matter how realistic, informed or smart we think we are.

I know this because I was in deep denial about my son’s autism and intellectual disability for a VERY long time. I thought of myself as reasonably analytical, yet it’s almost embarrassing how deluded I actually was.

How to explain my magical thinking and impossible expectations? It’s not that hard, actually — not with the benefit of hindsight and some reading on the subject of denial.

“The main benefit of optimism is resilience,” notes Daniel Kahneman in Thinking Fast and Slow, his fantastic book about how we think and decide. In my experience, denial helps us stay optimistic, and thus more resilient. It acts like a barrier to grief and fear — in my case, grief over the child I thought I wanted and fear of an unknown future I believed would be awful.

This barrier, though strong, is not an impenetrable shield. It lets some information in while making some of the negative feelings bounce off so that they do not paralyze us. In my case, the denial barrier let me dismiss, to a level I could cope with, the possibility that Diego might have an intellectual disability. However, it conveniently let in the autism part. After all, Diego was undeniably deeply affected by something.

I could handle autism because there was much information about therapies and treatments that supposedly “cured” children with autism, or rendered them “indistinguishable from peers.” Plus, in the unlikely event that Diego was not cured, thought I, at least he would improve so much that he would just grow into a quirky adult, with interesting idiosyncrasies, like so many successful people out there.

I just could not accept mental retardation, which was the term used throughout Diego’s childhood. Denial conveniently kicked in, clouded my reasoning and gave me some measure of resilience. I could explain away Diego’s low IQ scores many different ways. Diego was tired when tested. He lived in a dual-language environment. He was a terrible test taker. IQ scores could change as children developed, couldn’t they? However, my most reassuring and logical reason always was that Diego’s “autistic” behaviors got in the way and necessarily rendered the scores unreliable.

Bottom line, I just could not accept it. Mental retardation happened to other people’s children, not to my child.

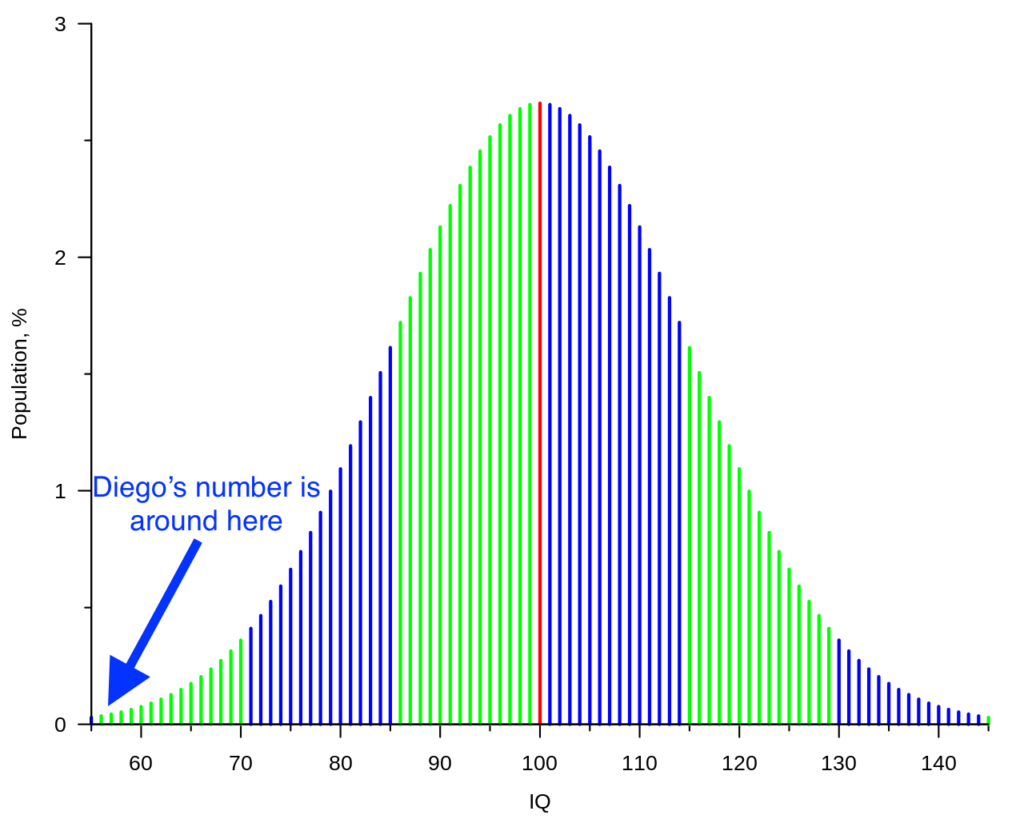

Like it or not, though, what can happen to anyone can happen to us, and what can happen to anyone’s child can happen to our own child, whether it’s something that brings us joy or brings us despair. For instance, what if Diego had been found to have a superior IQ? Well, that I would have accepted and celebrated, even if the scores were equally improbable.

The only difference is that I was told a number at the opposite end of the Bell Curve, so I went into denial mode instead. Which brings me to what Kahneman calls “the possibility effect,” which involves our tendency to think that we will beat negative odds and that statistics do not apply to us.

Which brings me to what Kahneman calls “the possibility effect,” which involves our tendency to think that we will beat negative odds and that statistics do not apply to us.

IQ scores under 70 usually mean that there’s an intellectual disability. I did not reject the concept itself, just that it could apply to Diego, even if he repeatedly tested way under 70. This makes no sense NOW, but it made good sense when I was in deep denial.

I also overestimated the probability of unlikely outcomes. When Diego was 7 years old, the Lovaas study used to be frequently cited. Lovaas claimed that early intensive intervention based on the principles of Applied Behavior Analysis could lead to the “recovery” of about 47% of children diagnosed with autism.

Never mind that the children in the study were half Diego’s age and received far more intervention hours. Never mind that the study’s success rate was questioned. I managed to ignore all this and to feel quite certain (94% certain?) that Diego would recover — a statistical impossibility given that only 47% were deemed “recovered”. I approached most interventions using the same twisted reasoning. I even sought improbable outcomes to overestimate, always convinced that Diego would be the exception and never the rule.

You’d think that someone would have tried to set me straight and bring me to my senses, wouldn’t you? The truth is, though, that no one likes to be the bearer of bad news, and that many of those who know we are in denial choose not to confront us. They remain complicit because they have witnessed the tremendous power of denial. They know that if they challenge us, they may, in the best of cases, merely be ignored, and, in the worst of cases, incur our wrath. Either way, they know from experience that we’ll get there when we get there.

Striking the right balance when faced with parental denial is next to impossible. I remember enumerating my unrealistic goals for Diego to the head of a fantastic autism clinic where Diego went for therapy. The clinic founder kept nodding and saying “Sure, sure…” as I spoke. He knew, but he did not confirm or deny.

I also recall a school administrator who, perhaps with good intentions, expressed that Diego would not be reading at grade level by the time he reached whatever grade I was aiming for. Was I ever upset!

Of course, there are those with perverse intentions who exploit our vulnerability and get to our wallets by promising impossible outcomes. Hint: anything that sounds too good to be true usually is.

Finally, there’s the media, which feeds our denial by over-emphasizing the exception and, in the case of autism, the very high functioning. I guess the most popular stories are those of children who overcome all the odds and dire predictions.

One good thing about parental denial is that it tends to decrease gradually. In most cases, we don’t just wake up one day and suddenly realize our delusion. Our hopes are malleable and change over time, often without us being aware of it. Denial gives us some time to adjust.

In the end, I believe denial is both a human need and a pitfall in human reasoning.