One September morning in 2022, while waiting in line at a Venezuelan Embassy, I befriended a man by the name of Ivan Daniel. He was the person right before me, number 14 I reckon, as I was number 15 on the list each of us jotted our names on when we arrived and took our place.

Everyone in line had been summoned on that specific day to renew their Venezuelan passport at the Embassy of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela in Mexico City. We had that in common, in addition to all of us being one of the millions of Venezuelans who have emigrated in the 2000s, around 25% of the population, according to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which is hard to fathom. Most of us came from far away since there are currently no formal diplomatic relations between Venezuela and many of our adopted countries.

Still, we would have bonded anyway, no matter why or where the line. We Venezuelans are people of the line, especially when it comes to affairs related to documentation.

Having established my place in the line -who was in front of me, who was in back of me, and who was in front and in back of them– I joined the ongoing conversation about what we should have brought and commiserated over how counter, no, anti-intuitive the online passport renewal platform, known as Saime, was (Saime: Servicio Migratorio de Identificación, Migracion y Extranjeria).

Few people had figured out how to get to the page that listed the requirements, so most of us had relied on information from friends, relatives, or acquaintances of distant friends and relatives who’d recently gone through the process. Recently is key here, as what’s required is a moving target. My husband, Cesar, had traveled to Mexico for his passport one year prior and one had to assume his intel was outdated.

At any rate, I’d scarcely been in line for three minutes when I discovered I should’ve brought a copy of either my (expired) passport or my national ID card.

Not that I’d failed to gather good intel. I had an optimal source, Miriam, who’d returned from Mexico less than two weeks earlier. Miriam and her husband, of all people, would know. They were desperate for a valid passport, seeing as they’d been “stuck” in the U.S. for years due to issues around their one and only passport.

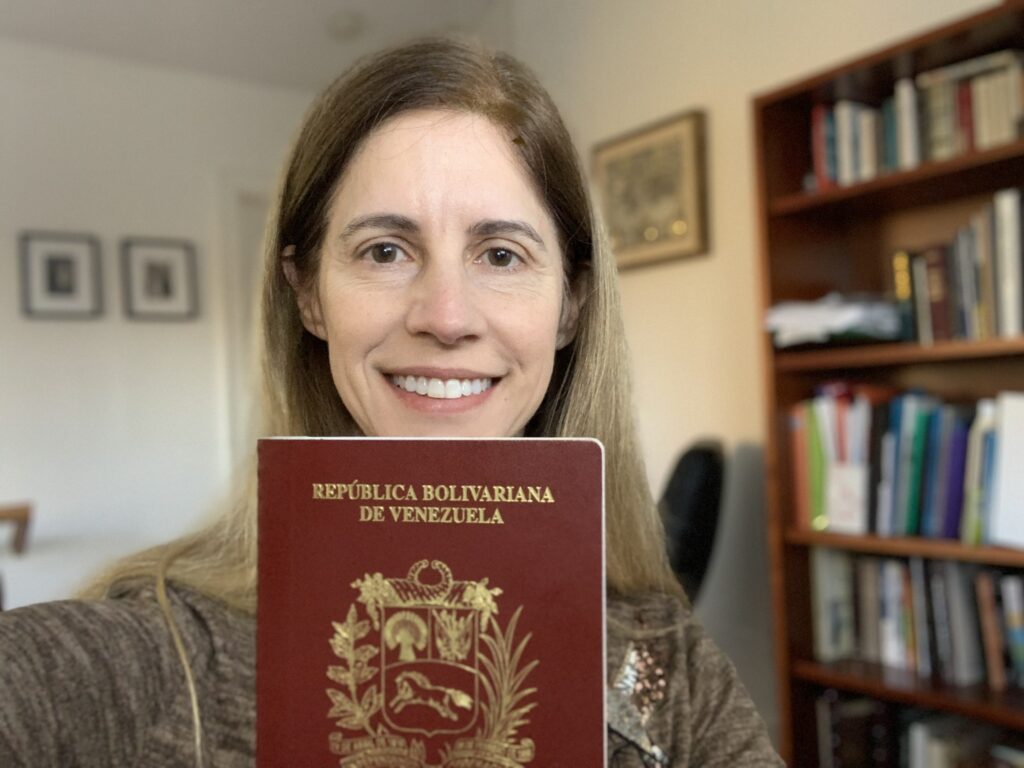

Me, I have three passports: Venezuelan, American, and Italian. I’d attribute 84% of this privilege to luck and 16% to a high degree of diligence stemming from a deep-seated fear of statelessness.

As it happens, Ivan needed the printout of our summons form, which included personal information and, most importantly, a QR code. It had taken me a while, but thanks to Cesar, who’s sort of a Saime platform whiz, I’d succeeded in locating my form. I can help you with that, I offered Ivan.

The Art of Asking for Help

After plotting for a bit and defining our spots in line with our fellow Venezuelans, we searched for a place to print his form and photocopy my document. We walked to two nearby copy centers to check if, by any chance or by the grace of God, they were open at 5:00 AM even though Google Maps showed opening time was 9:00 AM.

Because you never know, and because faith moves mountains.

Finding both closed, I proposed begging for help at a nearby Hilton Hotel, a very nice one, as the embassy is in Polanco, a lovely upscale Mexico City neighborhood.

I asked for help the way my mother would, prefacing the request such that the other person knows their very small action will make a life-altering difference. Like I’m serving them on a silver platter a golden opportunity to do good.

“Muy buenos días Señor,” I said to the gentleman at the lobby counter. “I have a huge problem and I was wondering if you could possibly help me out. You see, I need a copy of this one page in order to renew my passport.”

“But of course,” he replied, “I’ll be right back.” And just like that, I had the photocopy in less than 15 seconds.

And when I thanked him, “Infinitas gracias, señor,” my savior said, “De qué. Para servirla,” which means, literally, “What for. At your service.” I really like Mexican people. They are soft-spoken and kind and make you feel like royalty.

I am now waiting for my passport to be issued. I just need to periodically check the Embassy’s Twitter account, which posts the national ID card numbers of people whose passports are ready. The notification method makes perfect sense considering the playful process one gets to experience at the embassy in Mexico City.

Let’s start with the list we wrote our names on as we arrived. Who taped the paper for it by the front door of the building? My first guess was it must have been the first person to arrive. Then again, while some people would think to bring tape and a blank sheet of paper to an embassy appointment at a normal time, no one would do so at 3:00 in the morning. No, it had to be that an embassy employee posted the sheet the night before, which made me wonder what would have happened had it rained or been windy overnight. Anyway, I never asked.

Once you entered the building, they had you sit on rows of chairs -in line order obviously- and wait for your turn. They called people into a different room two and three at a time, with the rest of us standing up and sitting again two chairs down. It was reminiscent of playing musical chairs except with no music or change in the number of chairs. You got to play three times, for, after the waiting area, there were two more stations to visit, at every one of which officials treated you politely and professionally.

By the time you exited, you were like, “Hey this was fun. Again please!”

People of the Line

It is with a sense of sweet nostalgia that I call Venezuelans people of the line. It’s part of our culture. Lines train us in the practice of patience and acceptance. They spawn entrepreneurs and are the setting where caring, short-lived friendships emerge.

Depending on where the country has been in its grand revolutionary plan, Venezuelans have lined up to vote, buy rice and sugar, fill up their gas tanks, apply for a passport or get a permit to exit the country.

My husband had to get such a permit in early 2021 when he got into the country with his expired Venezuelan passport. They let you in but won’t let you out -unless you have a valid passport from another country and your Venezuelan passport renewal is “in process,” which was the case for Cesar. Also, like me, he has the luxury of having three passports.

At any rate, Cesar woke up before dawn to line up at the Saime office in Caracas to get said permit, and later recounted to me the “line culture” we’ve perfected. The line in Caracas was easily twenty times longer than in Mexico, and there was no sign-in sheet. People simply took mental note of who was in front and back of them and respected the arrival order.

Of note, Cesar discovered, a person could forgo most of the line by paying someone who makes an honest living standing in line to save a spot for others.

There’s communism for you, a system where standing in line is a job. The going rate then was $20. Yes, 20 U.S. dollars because communism can turn into the most savage and inhumane capitalism where everything’s transactionable and the only currency is hard currency.

Who wants in?

Then there are the micro-entrepreneurs who sell candy or laminate your documents- all caught on video in this Instagram reel by blogger/photographer Diego Vallenilla.

“Gestores” round out this market ecosystem. They are “facilitators,” folk who somehow -through connections, or real expertise involving the Saime platform and the ever-changing requirements and steps- will help you get your passport, charging anywhere from $100 to four-figure fees.

In Caracas, a handful of exceedingly polite Saime employees walked along the line checking people’s documents. Almost all the wait time took place while in line. Once you walked into the Saime office, you were processed with Swiss-like precision and utmost professionalism by Saime officials. Cesar was in and out in three minutes.

What with the professionalism and efficiency once you’re being processed, and the curiously entertaining nature of the wait, you almost forget why anyone would ever think to leave the country. Everything’s just dandy here! How come millions have emigrated?

Whyever did I leave? Maybe I shouldn’t have?

And here’s where I go off imagining alternate universes and what my life may have been like in each.

Finally, in line, you also get to know a person. You bond.

During the brief time I spent with Ivan Daniel in Mexico City, I learned that he had arrived in the U.S. pre-Chavez, intending to stay for just one year. Here’s how that year turned into 30+ years:

As a teenager, his Abuela had made him attend catechism classes to receive the sacrament of Confirmation. (A boy can’t say no to his Abuela.) The priest, who happened to be American, invited a few students to come to Minnesota with him -the sort of thing that could happen back in the 1990s when Venezuelans easily got visas to travel to the US.

The kids were hosted by friends of the church for an entire school year, at the end of which all but Ivan went back. The school year came and went and Ivan wanted to stay. Luckily, one of his school teachers took a liking to him and continued to host him through high school. Well, one thing led to another and another. Ivan stayed in Minnesota and in time became a U.S. citizen. A heck of an immigrant story, am I right?

It All Starts with a Passport

It’s hard for Americans to grasp the value of a passport, any passport, even one -no, especially one issued by the autocratic government of an economically ravaged country thousands of people are leaving, many of them on foot and carrying only what they can haul through miles of dense jungle. It’s a cruel reality that for citizens of autocratic countries, it’s a good deal harder to obtain a passport than for, say, Americans to get a United States passport.

I dare bet that the more repressive the country, the more obstacles citizens face. Ask a Cuban or North Korean national.

I tried to explain it to a couple of co-workers but their eyes glazed over. I would take a day and a half off from work to fly to Mexico City, where I would spend 23 hours. During that window of time, I would show up at the Venezuelan Consulate on the exact date indicated in the email I’d received just two weeks earlier. I had to drop everything and take the appointment. Who knows when I’d get a new one and how much notice I might get next time?

Immigrating to another country requires a good deal of persistence, luck, and money, usually a lot of money. When I hear Americans say they’ll move to (insert country, though it’s usually Canada) if so-and-so wins the election, I mentally roll my eyes. People, it’s not that simple.

Do you think countries have an open-door policy just for Americans like you who want to take up residence? No, even Americans have to go through a process. And by process I mean copious documents gathered and submitted and a long list of requirements fulfilled so you can be approved, but only for two years from the moment you submitted the paperwork, so by the time you get the approval you’re due to renew the paperwork and gather it all anew.

And wouldn’t you know it, one of the documents you’ll unquestionably need is a passport.

It all starts with a passport.